You will be equipped to compete in a modern-day contest of courage and skill that will, win or lose, bring you as close to those brutal matches of old as you can get. Full-contact, no-holds-barred competition that utilizes weapons without benefit of protective armor. Matches that resulted in permanent injury and disability, not just to one combatant but often both. A brutal test of skill and courage that for on participant ended all to frequently in death.

Kali stickfighting was banned in this original form by U.S. forces occupying the Philippines during World War II. Kali stickboxing, a modified version of those matches fought by the escrimadors and kalista of old, continues today, perhaps not as lethal, but just as demanding and exciting. Originally, matches allowed participants the use of sticks called “bahi” or “kamagoon”. These sticks made from ironwood, a wood heavier and harder than rattan training sticks used both then and today, were fashioned by the kalista into the shape of a sword.

In contrast to the baston used in today’s stickboxing, these early versions had in effect two striking surfaces, the flat, broad face and the narrow knife-like edge, either of which was capable of inflicting severe injury upon one’s opponent. Unlike those of old, today’s practitioners, in addition to their skills and courage, rely on lightweight armor for protection. What survives basically intact, however, from the art’s original form, are its rules and procedures, its techniques and methods.

Credit for the modern design of kali stickboxing belongs to guro Ted LucayLucay, son of the late Lucky LucayLucay, who has furthered his father’s kali and boxing method through the implementation of new training procedures of his own. Unlike other escrima systems, in kali boxing the stick work although an important component, is but one element of the overall method of attack and defense. At the core of this system lies the body mechanics of boxing. When using any weapon, one well-placed strike could conceivably end a life, so in addition to taking a true and realistic approach to the art, today’s practitioner must also factor in safety during training and in actual competition.

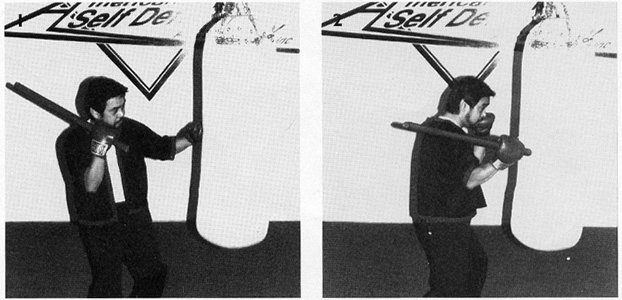

Equipment training is an essential element in the development of the stickboxer’s skills. Guro Ted Lucaylucay demonstrates (1-2) how to use the heavybag in conjunction with the stick.

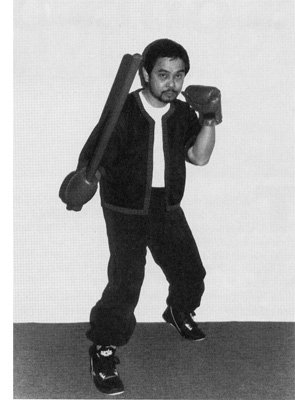

The kali boxer now uses a 29-inch long cylindrical nylon stick padded with canvas. Headgear used consists of a wire mesh face cage attached to boxing-style headgear or a hockey-type helmet. The weapon hand is protected by a padded glove. The other hand is gloved as well for both blocking and punching. Elbow pads are used but most often knee pads are not because of the limitations they place on mobility. Offensive knee strikes, though legal, are delivered at less than full power, with the objective being not to injure but to score points. The weapon is held in the lead hand. Strikes can be delivered with the tip, the center and the butt of the stick as well as with the hand that grips it. The rear hand is used extensively as an offensive weapon in conjunction with both elbows and knees.

Forty percent of the knockouts in real stickfights where credited to the use of the rear hand.

Various tools come into play at various ranges. At long range are kicks and strikes with the end of the stick. At middle range are hits with the center of the stick, punches from either hands or elbow and knee techniques. Close range allows for puno strikes, head butts, throws, takedowns, and ground fighting procedures where submission holds can be utilized.

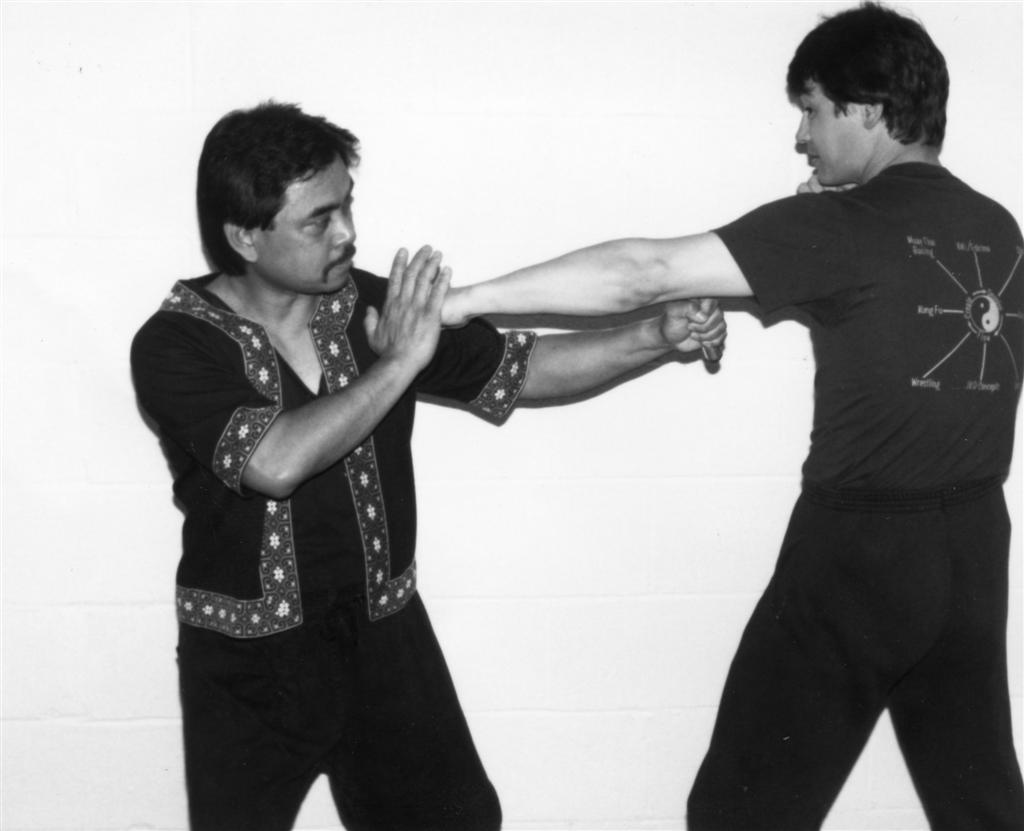

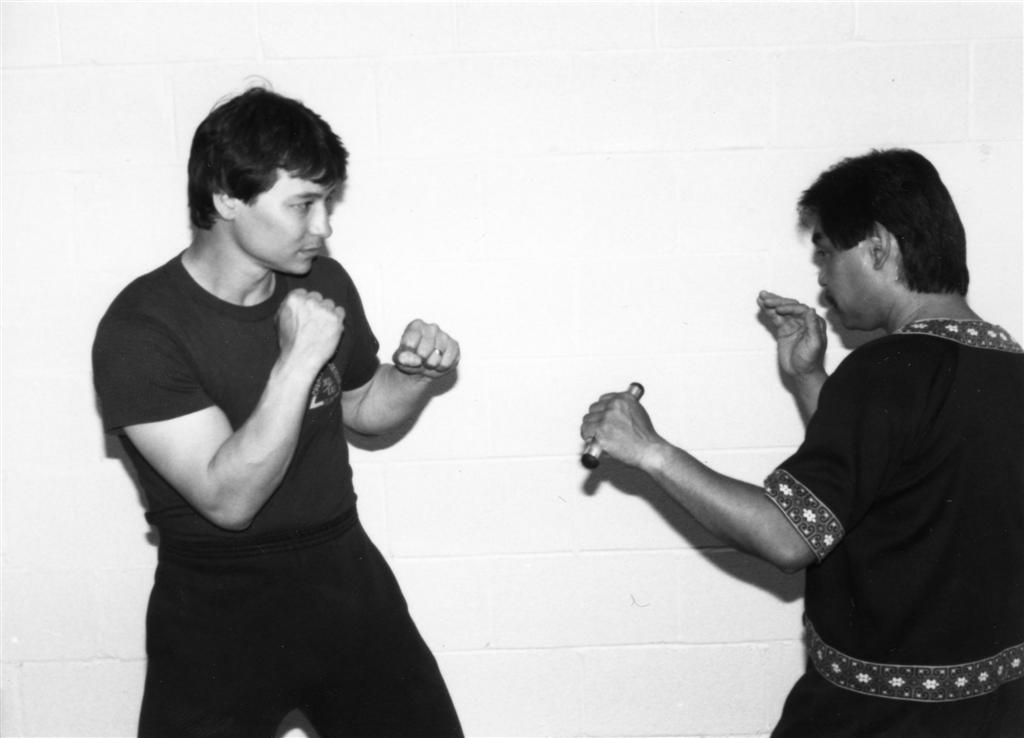

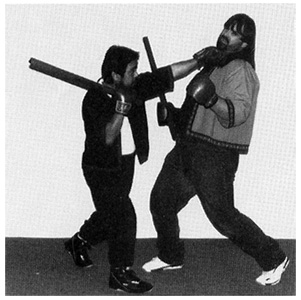

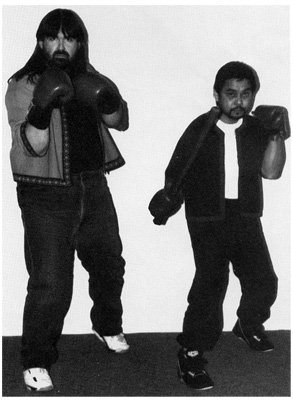

The on-guard position of the kali stickboxer resembles the posture of the Western boxer.

Unlike the old form where fighting continued until one combatant is either disabled or dead, in current competition fights consist of rounds timed at either two or three minutes depending on the class and skill level of the fighters.

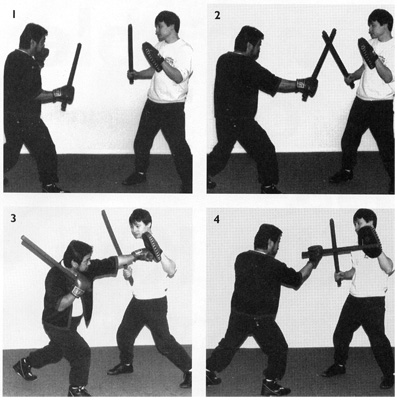

Focus mitts are used extensively in the kali boxer’s preparatory training. Here we see guro Ted closing the gap with the stick jab and following up with the cross and flip/hit combination.

The number of rounds to be fought and allowable target areas are pre-determined prior to each match. A clinch or grappling situation, whether in a standing position or on the ground or even the loss of a weapon, are not cause for a break. The fighting continues until the sound of the bell or until a victor is declared. A winner can be decided in several ways; through an accumulation of points scored by strikes to legal target areas, through the inability of one opponent to answer the bell, by submissions or lastly by TKO or knockout.

Endurance, stamina and cardiovascular conditioning are attributes that a kali boxer must bring with him to the ring. Fatigue sets in rapidly if you have not prepared to spar with a stick. The use of the heavy bag, speed bag and focus mitts plays an important role in preparing the stickboxing. Grip strength and the ability to properly hold and maintain the weapon are of paramount importance. Lose your weapon and you will most likely lose that round, if not the match itself. In the old days, loss of one’s weapon more often than not equated to loss of one’s life.

Although not geared toward all martial artists, kali stickboxing has much to offer. As a practiced stickboxer you will realize an elevated skill level of the attributes that you brought with you, along with having acquired some new techniques unique to this style. You will be equipped to compete in a modern-day contest of courage and skill that will, win or lose, bring you as close to those brutal matches of old as you can get, and still live to fight another day.

From Martial Arts Ultimate Warriors magazine, June 1995.

Article Author: Richard Lamoureaux Photos: Wes Bennett